Paradisus Terrestris

In the suite of paintings that he is now showing under the title Paradisus Terrestris – the earthly paradise – Johan Furåker focuses on Italian gardens from Antiquity and the Renaissance. The garden tradition displays a powerful urge to use greenery, gravel, architecture and water to recreate the world spatially, as a microcosm that gathers within it all of a culture’s mythologies, including its myths of paradise.

In 1967, the philosopher Michel Foucault gave a lecture that was to have a major influence on discourses about places of various kinds. He introduced the concept of the ‘heterotopia’ to describe a type of ‘other places’, places that probably occur in varying forms in all cultures. These are real places that contain within themselves the culture’s other places, stratified on top of one another in concentrated form. At the same time, they stand apart from the ordinary place. Foucault enumerates various examples of heterotopias, among them the cemetery, the museum, the library, Jesuit colonies in South America, and the garden.

Furåker introduces us to the garden as earthly paradise and as heterotopia via a number of picture-postcard-sized paintings inside a glass showcase. They reproduce diverse iconic fragments from tales about paradise, painted likenesses of more or less familiar images that in various ways recall the story of paradise: the capital of a medieval column showing Adam and Eve; Michelangelo’s depiction of The Fall from the Sistine Chapel; a scout making fire by using a harder wood to penetrate a softer one; and a cryonic capsule in which we can be frozen in the hope of eternal life, once science has solved the problem of death.

The pictures refer back to Furåker’s earlier works through their postcard format, through their lack of depth, and through the way that they lean against supports, as objects. The focus here is on narrative structures, on stories, and not on spatial attributes. They are deliberately static, frozen. It is through their character as objects that they become spatial. At the same time as referring to the past, on the level of ideas they point forwards to the direction taken by Johan Furåker’s new paintings, those hanging on the walls.

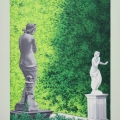

These are like his /?/ small panel paintings, but their format is larger, almost like windows, windows that open onto the illusion of a space that has perspective and depth; the space, greenery and gradually whitening sculptures of the garden, with topiary hedges that create boundaries both within the garden and with the surrounding landscape, thus forming the heterotopia, and evoking a sense of longing. The paintings are made from photographs, which gives rise to some pleasing distortions, in some cases coming close to the vertiginous. Simultaneously, we become aware of the problematic, illusory nature of reproduction. These are paintings from photographs in books – already representations in themselves – of arranged landscapes. It is as though additional layers had been placed over all the previous ones.

In a nod to Gerhard Richter’s colour-field paintings, Furåker also introduces paintings with grid patterns. Colour charts of all the shades of green that he himself has used when painting his earthly paradises: Hadrian’s Villa, the Boboli Gardens, Villa I Tatti. The human eye can distinguish more shades of green than of any other colour, perhaps originally so that we would be able to survive out in nature; a visual sense well-adapted to the earthly paradise.

Måns Holst-Ekström

Critic, art historian and writer, attached to Lund University